Towards an anthropology of statelessness (Judith Beyer)

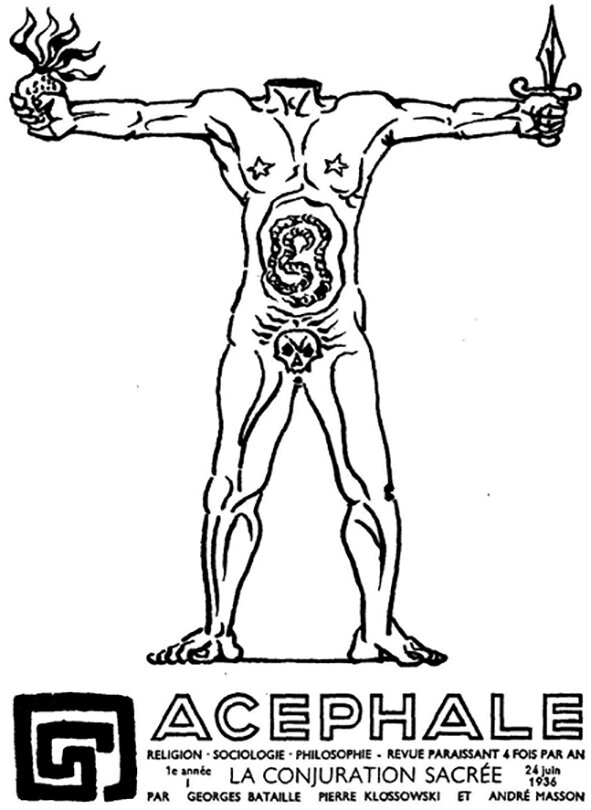

Anthropologists have historically dealt with stateless societies in the context of colonial politics of expansion and exploitation. Ethnographic monographs of the time centered on ‘acephalous’ ethnic groups or tried to grapple with understanding how groups organized themselves and interacted with one another without a clear leadership. After the demise of colonial empires, such ethnographic work has almost completely come to a halt. The state has come to tighten its grip on ethnic groups to such an extent that there is, by now, no place on earth that would not feel its often eerie presence. This includes hunter-gatherer societies and sedentary tribes in rural Africa and Central Asia as much as agrarian groups in Southeast Asia. However, statelessness as a condition of individuals and groups of people who are not recognized as belonging to any state, has remained a phenomenon worthy of anthropological attention and theoretization. Despite two UN Conventions against statelessness (1954, 1961) which many states have ratified, statelessness not only continues to exist across the world, including in Europe, the numbers of stateless individuals are even increasing. Statelessness remains one of the most overlooked human rights violations as it effectively deprives individuals of their ‘right to have rights’ as Hannah Arendt, drawing on Immanuel Kant, put it.

In this project, I work towards establishing an anthropology of statelessness that focuses on stateless subjects and scrutinizes the public portrayal of the stateless as an amorphous mass of ‘nowhere people’, ‘legal ghosts’ or ‘aliens.’ My aim is to research statelessness not as a historical leftover of group encounters with (colonial) states, but as an existential human condition of currently at least 15 million people worldwide that also allows for a novel perspective on the very concept of ‘the state’. I argue that an anthropology of statelessness can fruitfully expand the well-established subfield on the anthropology of the state, but it requires its own theoretization. Statelessness can neither be found at the ‘heart of the state’ (Fassin) nor at its ‘margins’ (Das and Poole), where anthropology has so far located its objects of inquiry when studying the state tangentially (Harvey). Statelessness rather points to what I – with Jacques Lacan – regard as a structural lack that is crucial for how we imagine and theorize the state (Abrams) and its state effects (Mitchell). While (I)NGOs, activists, legal practitioners and scholars mostly treat statelessness as an ‘anomaly’ for which a technical (juridical) fix could be found, I argue that statelessness posits a structural lack that cannot be ‘filled’ or ‘fixed’ and that it is ‘the state’ itself that contributes to the phenomenon.

My project draws on ongoing ethnographic fieldwork with stateless individuals, NGOs and lower-level bureaucrats in Germany and Europe. I also utilize court materials I obtain in my role as a country-of-origin expert concerning asylum cases of stateless individuals in the UK.